Share on Pinterest

Share on Pinterest- Previous studies have shown that COVID-19 impacts brain health, but the details are still relatively mysterious.

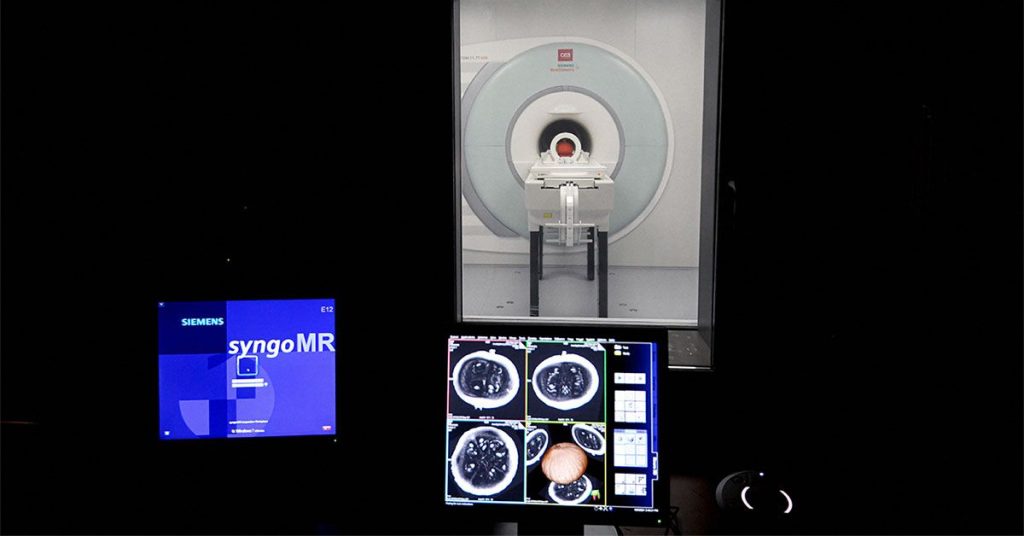

- A new study takes a closer look using the latest scanning technology.

- The authors conclude that damage to the brainstem associated with infection may help explain some of the symptoms of long COVID.

Following infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, some people experience long-term symptoms, including breathlessness and brain fog.

Scientists have attempted to pin down the precise changes in the brain that might be behind these issues, but results have so far been inconclusive.

A new study using the latest scanning technology focuses the search on the brainstem, a brain region responsible for controlling breathing, among other vital functions.

The researchers identify distinct changes in this brain region in people who were hospitalized with COVID-19. They also showed that the damage is more pronounced in those who experienced more severe disease.

Their results appear in the journal Brain.

Earlier research has shown that severe infection with SARS-CoV-2, leading to hospitalzation, is associated with changes in the brain, including:

- microhemorrhages, which are small bleeds in the brain

- encephalopathy, characterized by brain dysfunctions, such as confusion or memory loss

- white matter hyperintensities, which are abnormalities in the coating of some neurons, and which also appear in some cases of dementia.

Research also suggests that COVID-19 is associated with changes in the brainstem. The brainstem is the link between the brain and the spinal cord. It balances many of the key functions essential to life.

“The brainstem is responsible for controlling basic autonomic functions like breathing and heart rate,” one of the study’s authors, Catarina Rua, PhD, research associate in the Department of Clinical Neuroscience at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, told Medical News Today.

“These functions regulate our vital body functions, so they are mechanisms we do not control consciously,” she continued.

Some scientists have proposed that damage to this brain region might help explain why some people experience long COVID symptoms, which include:

- fatigue

- brain fog

- breathlessness

- mental health changes.

However, according to the authors of the new study, previous research has “not shown consistent brainstem abnormalities at follow-up.”

So, this time, the scientists used the latest scanning technology to investigate brainstem changes associated with COVID-19 in new depth.

The researchers used a relatively new scanning technology called ultra-high field (7T) quantitative susceptibility mapping.

Rua explained how these 7T scanners work and why they are useful for this type of research. She told us that:

“7T MRI scanners are more powerful than clinical 3T scanners in that they have increased sensitivity, so we are able to probe the brainstem at resolutions below the cubic millimetre.”

This sensitivity allowed the researchers to see microscopic changes in the brainstem that are impossible to spot using other scanning methods.

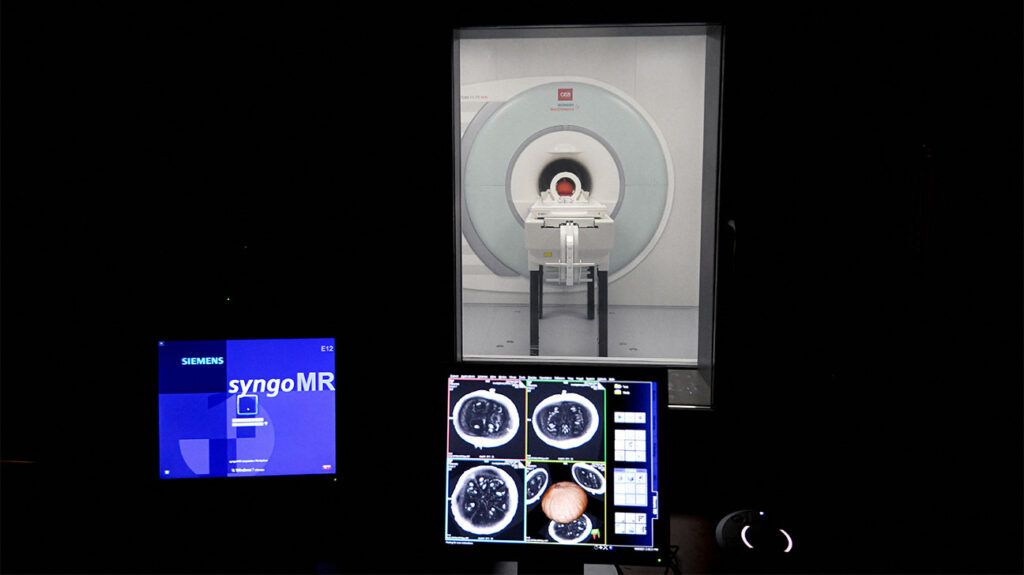

The scientists recruited 30 people who had been hospitalised with severe COVID-19. They scanned their brains between 93 and 548 days after hospital treatment. They compared their scans with 51 age-matched people who had not had a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

They found that the major regions of the brainstem — the medulla oblongata, pons, and midbrain — all had abnormalities linked to brain inflammation. As the authors explain, these differences between healthy participants and those who had experienced COVID-19 “are consistent with a neuroinflammatory response.”

Interestingly, some of these abnormalities were in a region that is central for controlling breathing called the “medullar reticular formation.“

“The fact that we see abnormalities in the parts of the brain associated with breathing strongly suggests that long-lasting symptoms are an effect of inflammation in the brainstem following COVID-19 infection,” Rua explained in a press release.

The scientists also showed that the abnormalities were more pronounced in people who had experienced the highest levels of inflammation during COVID-19. Similarly, those with less severe COVID-19 and shorter hospital stays had fewer brainstem abnormalities.

In the months following COVID-19, people often report fatigue, shortness of breath, coughs, and chest pain. The authors believe that the brainstem changes they spotted may make people more likely to experience these symptoms or at least make them worse.

MNT also spoke with Jeffrey Langland, PhD, a professor of research at Sonoran University of Health Sciences, who was not involved in the study. We asked how the SARS-CoV-2 virus reaches the brain.

“It has been shown that the virus can infect olfactory neurons and travel from the periphery into the the central nervous system [brain and spinal cord],” he explained.

Olfactory nerves enable our sense of smell; they travel from the inside of the nose to the brain.

“Once in the [central nervous system],” Langland continued, “the ACE-2 receptor that the virus uses to infect cells is present on cells in the central nervous system, so the virus can infect these cells and lead to damage, which is sometimes permanent in long COVID cases.”

However, the authors of the new study explain that to cause damage to the brainstem, the virus does not need to directly enter the brain.

In fact, they write that “in most cases, there is no evidence of direct viral infection” in the central nervous system. Rather, inflammation in the brain is a response to the infection in the body.

The study does have certain limitations. As the authors explain, the study is quite small. This was primarily because recruitment was challenging at the time of the study, which began before COVID-19 vaccines were available.

Also, the brain scans were taken at just one point in time. The authors write that following up patients at a later date would provide valuable insight into whether the brainstem abnormalities persist.

Speaking about the results of the study, Langland told MNT that they “increase our understanding of how the virus is causing the damage, but how to prevent that damage or repair it, is another area of research” — there are still many questions to answer.

However, Rua and her colleagues are continuing their investigation. “We collected a very rich dataset from these participants in this post-hospitalized recovery phase, so we are still in the process of analysing other MRI data,” she told MNT.

The scientists also hope that this advanced 7T scanning technology might help researchers gain new insights into other neurological conditions that involve inflammation in the brainstem, such as multiple sclerosis.

Source: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com

More Stories

Classic and green Mediterranean diets may help slow brain aging

Rheumatoid arthritis linked to changes in the gut microbiome in new study

Could taking fish oil supplements help lower cancer risk?